Deserted Medieval Villages

CHIPPING DASSETT

Burton Dassett lies midway between Warwick and Banbury. Its most prominent landmark is the medieval stone tower which stands on the ridge of the Burton Hills. Few of the many visitors to Burton Dassett today will realise that around the Hills there was once a thriving market town, known as Chipping Dassett, which in the early 14th century was one of the largest places in Warwickshire. More

Deserted Medieval Settlements in the Local Area

(Script of talk given by Liz Newman to the Group at its Meeting on 10th May 2010)

Introduction

The subject of tonight’s talk is the number of villages and hamlets in the local area which were depopulated in rhe medieval period and turned over to sheep pastures and, in some instances, replaced by a country house set in parkland. Before we start, I should like to take you on an imaginary journey. From Warmington, let’s drive along Camp Lane, noticing the shrunken settlement of Arlescote, below on our right. We are following the boundary between the parishes of Warmington and Ratley with Upton, from ancient times included in Ratley parish. Driving through Edgehill we reach the T-junction with the parkland of Upton House straight ahead. In the 13c. there were seven men holding land in the village of Upton. One was called John de Sokerswelle. If we now turn right, Sugarswell Farm, off to the left, marks the site of another medieval settlement, but we’ll carry on down Sunrising Hill. Two deserted settlements lie to our right, first Westcote and a mile further on, close to the first cross roads, Hardwick. These were both small villages within the extensive parish of Tysoe.

We will turn left and drive through Tysoe. Beyond Tysoe lie Compton Wynyates, where 26 households lived in the 13c., and Chelmscote, a hamlet of Brailes but big enough to have had its own chapel.

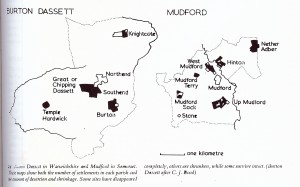

Returning to Warmington, let’s drive NW up the B4100. After a few miles we reach the parish of Burton Dassett – aptly described by Dugdale as “a parish somewhat spacious”. That part of the parish which lies to our left has been recolonised by an army camp. Until WW2, there were three isolated farms, Owlington, Marlborough and Frog Hall, but in the 13c. the Knights Templar of Balsall had eleven villein tenants working this land. On our right the important market town of Chipping Dassett has disappeared.

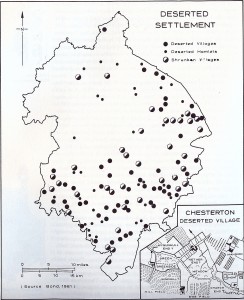

Travelling further north, over to our right, midway between Knightcote and Bishop’s Itchington, stood Nether Itchington – gone and its parish church demolished by the 1640s. Bishop’s Itchington was to become the main settlement in that parish. Another deserted place, one of the twin settlements of Moreton Morrell lies over to our left. Next on our road lies the parish of Chesterton with Kingston, again an extensive parish. There were five settlements in the early medieval period, but now only a few scattered farms.

Returning to Warmington and striking out through Mollington, turn north up the Banbury-Southam road. Soon the emptiness of the countryside is particularly marked. Over to the right is the site of Clattercote village, cleared away at an early date in the 12c. to make room for Clattercote Priory – today a farmhouse and a few modern cottages. Continuing north, the present-day village of Wormleighton lies to our right on high ground, with an extensive deserted village dropping down the side of the hill beyond the church. As we continue north along the main road, the deserted settlements of Watergall and Chapel Ascote are on our left, while on our right are Wills Pastures, Upper and Lower Radbourne and Hodnell.

The family who owned all theses depopulated places by early Tudor times were the Spencers – not necessarily the depopulators but a family which was among the most successful of a new race of graziers. The family owned no fewer than fourteen contiguous parishes here in Warwickshire, as well as many in Northamptonshire. They made their main home at Althorp, one of the three great houses of that county, built on a DMV and built too upon their wealth derived from grazing sheep and cattle. The Spencers bought Althorp in 1508 and by 1547 were grazing 1200 sheep on that estate alone.

Declining population

Why were settlements depopulated in the medieval period? Over one third of all the settlements in Kineton Hundred – ten main settlements and seventeen smaller secondary ones were lost. The deserted (and contracted) settlements of Warwickshire lay mostly in the corn-growing Feldon, the area south of the River Avon. And corn growing was labour intensive. With the Black Death of 1348/49, and the recurrent plagues of the following decades, labour was in short supply and was no longer prepared, or able, to cultivate land intensively.

Was the fall in population really so great? Demographers have calculated that in many areas the population was halved. It then continued to fall for a further 100 years. The plagues which succeeded the Black Death tended to be age-specific, killing children and young people while older folk had a measure of immunity, but were beyond child-bearing age. It was not until around 1520 that the population started slowly to increase.

There are no easily accessible sources to provide methods of calculating the local death rate at the time of the Black Death- no parish registers, for example, – but Dugdale writing in 1656 in his Antiquities of Warwickshire lists places parish by parish and gives the names of parish priests, the dates of their institution and the reasons for vacancies. There are many gaps within sequences, but nonetheless he provides information from an early date which is not available, as far as I am aware, elsewhere. Of the forty six parishes in Kineton hundred, the information is insufficient in twenty to draw conclusions. Of the remaining twenty six, in only six places did the incumbent clearly survive the Black Death period.

In twenty places a new incumbent (or more than one) was instituted to a parish ‘vacant because of the death’ of his predecessor in the years 1348-50. In five places there was more than one death Radway had four vicars between 1349-51, Fenny Compton had three in sixteen months, Barford had two and Cheriton had three in twelve months. At Ditchford Frary appointments were made in July and August 1349 because the first man died. No doubt the work of a conscientious parish priest took him among the dead and dying, but the figures are still staggering. Peasants living in rudimentary housing in a corn-growing area were surely just as susceptible to disease carried by fleas on rats.

Documentary sources

William Hoskins and Maurice Beresford pioneered the work on deserted medieval settlements from the later 1940s. This work has, in turn, led on to much further work, both by academics and in the archaeological field, on the morphology of villages – their desertion, shrinkage and movement – and not only in the medieval period. Before Beresford’s pioneering work – researching the documentary evidence, walking the ground and taking aerial surveys – many eminent historians were sceptical about the depopulation of settlements and the scale on which it had taken place.

William Hoskins and Maurice Beresford pioneered the work on deserted medieval settlements from the later 1940s. This work has, in turn, led on to much further work, both by academics and in the archaeological field, on the morphology of villages – their desertion, shrinkage and movement – and not only in the medieval period. Before Beresford’s pioneering work – researching the documentary evidence, walking the ground and taking aerial surveys – many eminent historians were sceptical about the depopulation of settlements and the scale on which it had taken place.

Of course people knew of places in the countryside around them where there were bumps and hollows and even sometimes attributed them to former settlement. Myths abound! “The village burned down” is perhaps the commonest explanation. In Rambles Round the Edgehills George Miller wrote in 1896 “Tradition says that a great part of the village of Burton Dassett was burnt down about 250 years ago” ie about 1650. He goes on to write “The field below the old chapel was once, it is said, full of houses.” But Miller knew of Belknap’s depopulation of Burton Dassett “It does not appear any great amount of harm was done.” I’m sure this would have been a very general attitude. Chipping Dassett in the first half of the 14th century was the third highest taxed place in Warwickshire. Of Temple Herdewyke, Miller wrote “Fields still bear the names connected with the old village and the face of the ground shows traces of the old village buildings ….. No-one can tell the cause of this desolation.”

Another myth, close to battle sites, is that “soldiers pulled the buildings down”. Or how about one I heard recently at Lower Ditchford (on the Gloucestershire/Warwickshire border) “They’ve never built on the old village site because the soil was poisoned by the Black Death”. The large flock of sheep and lambs appeared to be singularly healthy, grazing on verdant pasture!

Warwickshire is a fortunate county in uniquely possessing three documentary sources which are particularly helpful in the study of medieval settlement desertion. In 1279 Edward I appointed commissioners to undertake a survey, similar to the Conqueror’s Domesday survey of 1086, to record all landholders, from barons to serfs, with their dues and services. It was a somewhat abortive exercise and left only a fragmentary body of records. For places where documents survive, they tend to list only freemen and tenants-in-chief. Unusually the returns for the Warwickshire hundreds of Kineton and Stoneleigh survive, giving an apparently full census of all named householders in 1279, seventy years before the Black Death struck. Sadly the entries for Warmington, Arlescote, Shotteswell and part of Whitchurch are largely illegible.

The information from the Hundred rolls can be put alongside slightly later evidence from taxation records and the fortunes of individual settlements, including those to be depopulated, can be traced. these taxation records are preserved by the Exchequer in the PRO (National Archives), although the returns for smaller places tend to be grouped in with their larger neighbours. Manorial records, too, can be helpful in tracing the declining fortunes of about-to-be depopulated places. The records maintained by religious houses are more likely to have survived than those of lay men. (For example, no Burton Dassett court rolls survive, according to Christopher Dyer, while those of Westcote are preserved at Magdalen College Oxford. Westcote, although small had three manors; the lands of two passed from the Hospital of St John to Magdalen College at its foundation).

As stated above, Warwickshire is fortunate in possessing three unique documentary sources. The first is the Hundred Rolls. The second is a list,, written in 1486 (the beginning of the Tudor era) by John Rous, a historian and chantry priest of Guy’s Cliff, near Warwick, of places of recently depopulated. Rous listed sixty places within thirteen miles of Warwick which were depopulated, he asserted, within his lifetime, due to the greed of avaricious men, ‘destroyers and mutilators’. (Some scholars maintain that a few of these places had met their fate at a rather earlier date, so Rous was in those cases reporting a fait accompli rather than events personally witnessed). However Rous’s list gives us a definite date, 1486, by which depopulation had occurred in the villages he specified.

The third documentary source is Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire, published in 1656, and the first scholarly treatise written for any county. He recorded deserted sites within parishes, but could not be too denunciatory, or point too accusing a finger, because so many of his patrons (and many who provided him with information) were the descendants of evicting landlords! Local families which had taken their first steps up the social ladder by acquiring wealth as sheep and cattle graziers were just the men who in the 17th century became the local JPs and represented their county’s interests in Westminster. Country houses and their parks in many places stand on the site of the medieval village, the church, if it survived, became a private chapel and family mausoleum.

Representations on behalf of the dispossessed tended to fall on deaf ears, though a number of eminent folk pleaded their cause – and provide us with some memorable quotations – from John Rous in the 15thc. ‘ villagers left their homes weeping’, to Sir Thomas More in Utopia in the 16c. ‘ Sheep eat up men’, through to Oliver Goldsmith’s poem The Deserted Village, ‘Sweet Auburn! loveliest village of the plain’, believed to refer to the village of Newnham in Oxfordshire rebuilt as Nuneham Courtenay in the 1760s outside the park walls. Even today, to stand on the ground of a well-marked deserted settlement is a deeply moving experience. Commissions of enquiry were held in the early Tudor period and some depopulating landowners were fined. However only events post-1488 were taken into account and many earlier evictions thus escaped penalty.

Let us now look at some of the many villages in this locality which contracted in the four generations or so between the Black Death and when they came to the notice of John Rous, observing first the smaller settlements – the Herdwicks, Westcote, Brookhampton in Kineton, Thornton in Ettington and so on. As already stated the Feldon was grain-growing land, the granary for towns like Coventry and for areas like the Arden where little grain was grown at that time. But of course grain-growing without “cattle” – oxen, cows, sheep – was impossible; they were needed for tillage, haulage and manure. And a farming community could not survive without its supporting crafts – the miller and blacksmith spring to mind. But there was more to it than that. In the 13th. century in this area surnames were just being adopted and a fifth of the population had occupational surnames, likely to reflect the very jobs these individuals undertook.

Thus Newbold Pacey had a carter, a butcher, a basket maker, a carver and a painter. Idlicote had some of these trades and a brewer and an appleseller. Compton Wynyates had a thatcher and a mason. Walton Deyville had a cook and Nether Ettington, as well as several other trades, a tailor, a draper, and a slaymaker, making tools for weaving. The social fabric of small villages was unsustainable if the blacksmiths, millers, bakers and brewers died in the plague. The survivors of these small villages probably moved (willingly or under compulsion) to the larger, parent village.

For all peasants surviving the Black Death and subsequent plagues, life became even harder than before. How could you cultivate your strips of land, if all around the vacant plots of your dead neighbours were reverting to weeds? Who would do the communal jobs like scouring the ditches? Who would make up a team for co-operative jobs like ploughing or carting the harvest or carrying goods at the lord’s behest – all the work customarily demanded by the landlord? Who would buy the products of your husbandry or craft if half your market was gone?

Looking at the bigger settlement of Chipping Dassett, which totally disappeared, we can tell from the surnames which were emerging at the time the Hundred Rolls were written, the specialised nature of the occupation of some of its many residents Adam le Taylur, Thomas Mercer, Walter le Merchaund, Ralph le Merchaund and Nicholas le Lockyer (locksmith). Chipping Dassett, with its chartered market, was far from being a purely agricultural community, but all villages had and needed their craftsmen.

Very few settlements collapsed completely immediately after the Black Death, it seems, and many landlords tried hard to replace the tenants who had died. But the old social and economic order was breaking down; the survivors could seek tenancies on easier terms or lower rents, or move to towns if they had useful skills. Many landlords allowed some part of their holding to fall to grass – and therein lay temptation as the price of wool rose and the demand for grain, with fewer mouths to feed, continued to fall. A flock of sheep could produce much higher returns than the income to be derived from tenants’ rents.

The Feldon of Warwickshire was not alone in suffering depopulation and the area around both in Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire shared many of its characteristics. At the Norman Conquest, to the east of Warmington, lay Mollington and the large estate of the Bishop of Lincoln. In Banbury Hundred, Domesday Book lists just Banbury, Cropredy, Mollington and Wykham. In Cropredy the Bishop had eight undertenants and one can make a calculated guess which villages were implied. Today the Bourtons, Wardington and so on survive, but Prescote, Upper Prescote and Coton did not, or survive only as manor house or farm. Clattercote, as already mentioned, was a very early depopulation.

Towards Banbury, the settlement of Hardwick was depopulated – though very much repopulated in the last decade or so! Wykham was listed in Domesday Book and was a sizeable village being quite highly taxed in, for example, 1334, but by 1524 only three tenants were left and today Wykham Park covers the site.

Oxfordshire as a whole contains at least a hundred deserted settlement sites. Some, not too far from here include Brookend in Chastleton and Little Rollright. The Lea, at Swalcliffe, where now only Lower Lea Farm remains, was quite a late desertion with evidence of some, much reduced, occupation into the 17th century. Swalcliffe Lea is of particular interest because of evidence of significant Roman occupation on ‘blacklands’ and adjacent areas.

Some nearby settlements just over the Northamptonshire border suffered a fate similar to their Warwickshire neighbours. Appletree in Aston-le-Walls was probably always a small village, but has long been only a couple of farms. Purston and Newbottle, towards Kings Sutton, were both important enough to appear in Domesday Book but have long gone; flocks of 600 sheep and 1000 sheep respectively were grazing over the foundations of village homes by 1547.

Other deserted settlements already mentioned have evidence of occupation dating back to Roman times and earlier, as well as Swalcliffe Lea. Chesterton in Warwickshire, by the Fosse Way, is an obvious case, while Wykham, derived from the Latin ‘vicus’, is likely to have been a place of some administrative importance during the Roman occupation, and perhaps later, (see Margaret Gelling’s Signposts to the Past).

The study of why some villages contracted and some disappeared in the medieval period – 36% of all settlements in Kineton Hundred vanished leaving only a farm or two – is a fascinating one and each deserted site has its own individual history. Tonight I have sketched only the briefest outline. The plagues and pestilences of the fourteenth century produced economic and social disruption, but provided opportunity for those who could grasp it to change agricultural practices dramatically.

Sources

Domesday Book, Phillimore translation, vols. 14, 21 & 23

The Warwickshire Hundred Rolls of 1279-80, Stoneleigh & Kineton Hundreds

ed T John

The Antiquities of Warwickshire, Vol I

Wm Dugdale, 2nd ed 1730

The Deserted Villages of Warwickshire,

M W Beresford (Trans.Bham Arch Soc 1950)

The Deserted Villages of Northamptonshire,

Allison, Beresford & Hurst 1966

The Deserted Villages of Oxfordshire,

Allison, Beresford & Hurst

Medieval England An Aerial Survey,

M W Beresford & J K S St Joseph, 1958, 1979

A History of Warwickshire,

Terry Slater, 1981

Rambles Round the Edge Hills,

George Miller, 1896, reprinted 1967

Everyday Life in Medieval England,

Christopher Dyer, 1994

The Countryside of Medieval England,

ed. Grenville Astill & Annie Grant, 1988

Reading the Landscape,

Richard Muir, 1981

Interpreting the Landscape,

Michael Aston, 1985

Signposts to the Past,

Margaret Gelling, 2nd ed., 1988

Two case studies, Wormleighton and Lower Ditchford